Can Palestinians be wrong?

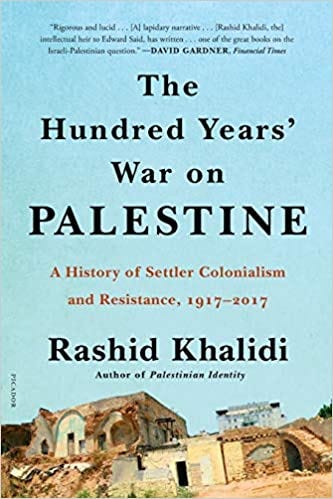

A book by a heavyweight Palestinian academic is riddled with errors

I first read Rashid Khalidi in college. The professor who assigned us the text was a Palestinian who often became emotional in class. “They told us the Iraqi army was coming to beat the Israelis and we left Haifa for the summer expecting to be back,” our professor said. “But we never went back.”

That assignment introduced me to Khalidi as a historian who was several notches above the average Palestinian intellectual, and certainly above American Progressives whose books on Palestine read like activism pamphlets rather than intellectual work. But the Khalidi I once read quarried the data to offer a comprehensive account. Khalidi today demands scholarly work from authors on Palestine/Israel, but does not offer one himself. Instead, this Palestinian-American historian mixes a personal memoir with a roadmap for Palestinian activism recommended to destroy Israel.

Khalidi’s book, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, suffers logical fallacies, absence of key events, and inadequate understanding of global affairs.

The author says that his great great uncle, Yusuf Dia Khalidi, sent a letter to the founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzel, describing Zionism as “natural, beautiful and just,” and adding that “who could contest the rights of Jews in Palestine? My God, historically it is your country!”

The younger Khalidi argues that Zionists often use this quote “in isolation from the rest of the letter,” in which the elder Khalidi warns “of the consequence of the Zionist project.” But here, the younger Khalidi commits a logical fallacy. Recognizing the right of the Zionists in Palestine is one thing, warning of the feasibility of their project is another. When Israelis cite the letter as Palestinian recognition of their right to the land of Palestine, they take nothing out of context.

Then, when narrating historical events, Khalidi leaves out key details. When he mentions Amin Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, he never hints at any association between Husseini and Nazi Germany, or Husseini’s meeting with Hitler.

When Khalidi writes about the 1967 war, he describes it as a master plan to control all of mandate Palestine, while conveniently leaving out details, such as Egyptian President Gamal Abdul-Nasser closing the Straits of Tiran — through which Israel imported 90 percent of its energy — an act that led to war. He also leaves out Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan’s statement that he expected Arab countries to call him to get their territory back, in return for peace. In response, Nasser convened the Arab League in Khartoum, and issued the famous “three No’s” statement that said “no (Arab) peace, no recognition, no reconciliation” with Israel.

Khalidi says that shortly after the Oslo Peace Accord, Israel increased its checkpoints. No mention that, a month after signing Oslo, the Palestinians launched a suicide bombing, and that in 1994, five Palestinian suicide attacks killed 38 Israelis. In 1995, while implementing Oslo was in process, Palestinian suicide attacks killed 39 Israelis. Khalidi never mentions Yehya Ayyash, “the Engineer” who planned these bombings. Instead, Khalidi associates Palestinian suicide attacks with the Second Intifada, in 2002, and even then, says bombings came “as a result” of Ariel Sharon’s “provocation,” after his visit to the Dome of the Rock.

Palestinian Hamas never gave peace a chance, and Arafat was either unable or unwilling to deliver security by stopping them, thus forcing Israel to forcefully escalate even while talking peace.

Khalidi’s “errors” are not only about Israel. When talking about Hezbollah, he describes it as growing “out of the Lebanese maelstrom.” Notwithstanding Hezbollah’s leaders publicly saying that they work for Iran, or that every academic work considers the Lebanese party to be an Iranian tool, Khalidi throws in his claim, unsubstantiated.

When talking about ethnic cleansing in Iraq and Syria, Khalidi keeps the culprit unknown: “Forcible transfers of population on a sectarian and ethnic basis have taken place in neighboring Iraq since its invasion by the United States and in Syria following its collapse into war and chaos.” A reader might think that America, not Iran and its militias, is responsible for Iraq’s ethnic cleansing, while in Syria, such atrocities just happen. Khalidi writes 250 pages about empathy, fairness and objectivity, but fails to mention war crimes by Iran and Assad.

A reader might be willing to forgive Khalidi’s “errors,” perhaps they were an unintended “lapse of memory.” After all, Khalidi is not an objective academic, but an activist who was on the official Palestinian negotiating team with Israel and who had ties to Palestinian leaders.

The book also shows inadequate Palestinian understanding of global affairs, past and present. In Khalidi’s mind, the Palestinian issue is clear and simple: An Arab majority once lived in mandate Palestine. Then alien Jews migrated en masse, expelled the Palestinians, and illegally constructed a sovereign state that they refuse to share with Palestinians.

But human history teaches us that an indigenous majority, in any land, does not always get the right to sovereignty. The Kurds in Iraq, Turkey and Iran are indigenous majorities in their defined territories, but never sovereign. The Arabs in Iran are also native, but their state (the size of Syria) was annexed by Iran in 1926, and their rights have been compromised since. Turkey annexed the Antioch Province (the size of the West Bank), in the 1930s, despite its Arab majority.

Khalidi cites three examples of colonialism — South Africa, Ireland and the US — and thinks that if Palestinians can make a similar case to the world, they can beat Israel. But if the US model is what Khalidi is looking for, the indigenous are nowhere near recognition as sovereigns. At best, they either enjoy autonomy on reservations or pledge allegiance to the American republic. Palestinians are not willing to pledge allegiance to Israel. As for Ireland, the conflict ended up dividing the country. In South Africa, racism was horrible and incomparable to the Israeli-Palestinian situation, no matter how hard the Palestinian intelligentsia tries.

Conveniently, Khalidi leaves out indigenous populations whose separatism never worked, such as the Scots and the Welsh in the UK, or the Catalans and the Basque in Spain.

Where Khalidi sounds misinformed the most is here: “The advantage that Israel has enjoyed in continuing its project rests on the fact that the basically colonial nature of the encounter in Palestine has not been visible to most Americans and many Europeans.” Hence, Khalidi says, “Dismantling this fallacy and making the true nature of the conflict evident is a necessary step if Palestinians and Israelis are to transition to a postcolonial future in which one people does not use external support to oppress and supplant the other.”

But this is not how global affairs go. Israel is not winning because Americans and Europeans have been duped, and, when told the truth, Israel will lose. Even if all Americans and Europeans believe the Palestinian narrative, sympathy alone does not influence global policy. Just look at Syria. All Americans and Europeans see the injustice befalling the Syrians because of their dictator, but none are willing to do anything about it because Syria is strategically unimportant. Similarly for the Palestinians. Even if their case is a slam dunk, why would America or Europe invest resources to change things?

If Khalidi can answer the above question, he will understand why global powers take Israel’s side. Israel has aligned itself with their interests as a reliable ally. Still, Western powers would not have been enough for the Israelis to win. America threw its weight behind its Iraqi allies, but these could never stand up. There is a crucial Israeli ingredient that Khalidi and most Palestinians never seem to notice: Democracy.

Since 1897, the Zionists have been electing their leaders like clockwork, with power always transferred peacefully and seamlessly. On the Palestinian side, Khalidi describes Arafat as “the head of Fatah [who] soon became chairman of the PLO Executive Committee, a post he retained, among others, until his death in 2004.” Thirty-seven years of Arafat’s undisputed leadership and failures, but Khalidi thinks that it is external bias toward Israel that enabled Israel to beat the Palestinians.

The final gem in Khalidi’s inadequate understanding of global affairs is his cheering for the rise of India and China. “Perhaps such changes will allow Palestinians… to craft a different trajectory than that of the oppression of one people by another.” If Khalidi thinks that Palestinian deliverance will be at the hands of China — with its genocide against the Uighur and veto against stopping Assad’s genocide in Syria — then, like generations of Palestinians, Khalidi still does not get it. And hence, Khalidi sounded perplexed: Why did his neighbor and colleague at the University of Chicago Barack Obama, who probably shares Khalidi’s view of Israel/Palestine, not enforce such view when he came president? Answer is that in foreign policy, national interests lead, and “the narrative” follows.

Palestinians will continue living in misery not because the world is misinformed, but because they fail to internalize the Greek wisdom, Know Thyself. Then, build a democratic movement that aligns Palestinian interests with bigger powers — including with Israel. That way, Palestinians will get a state, instead of spending the coming century, like the last, authoring books of frustration. Salam Fayyad tried it, but could not do it alone. Perhaps that is why Fayyad is not in Khalidi’s book, who prefers instead to hang on to words like colonialism, indigenous, Apartheid and Edward Said — words that make their authors feel good, but that will keep Palestinians living in misery.

My grandfather got killed fighting the invading Iraqi army - 750 miles from their border, and 8 miles from his home. I need ‘progressives’ to tell me again who tried go commit genocide in that war, and who were the invaders. Swallowing the propaganda of the Free Palestine cult for decades didn’t make them right; it made them the useful idiots of Islamist terrorists.

Can Palestinians be wrong? Yes, they have been making poor choices for decades and look where it’s gotten them